Consonance

Sometimes, as one is falling asleep, there may be a massive, involuntary jerk--a myoclonic jerk--of the body. Though such jerks are generated by primitive parts of the brain stem (they are, so to speak, brain-stem reflexes), and as such are without any intrinsic meaning or motive, they may be given meaning and context, turned into acts, by an instantly improvised dream. Thus the jerk may be associated with a dream of tripping, or stepping over a precipice, lunging forward to catch a ball, and so on. Such dreams may be extremely vivid, and have several "scenes." Subjectively, they appear to start before the jerk, and yet presumably the entire dream mechanism is stimulated by the first, preconscious perception of the jerk. All of this elaborate restructuring of time occurs in a second or less.

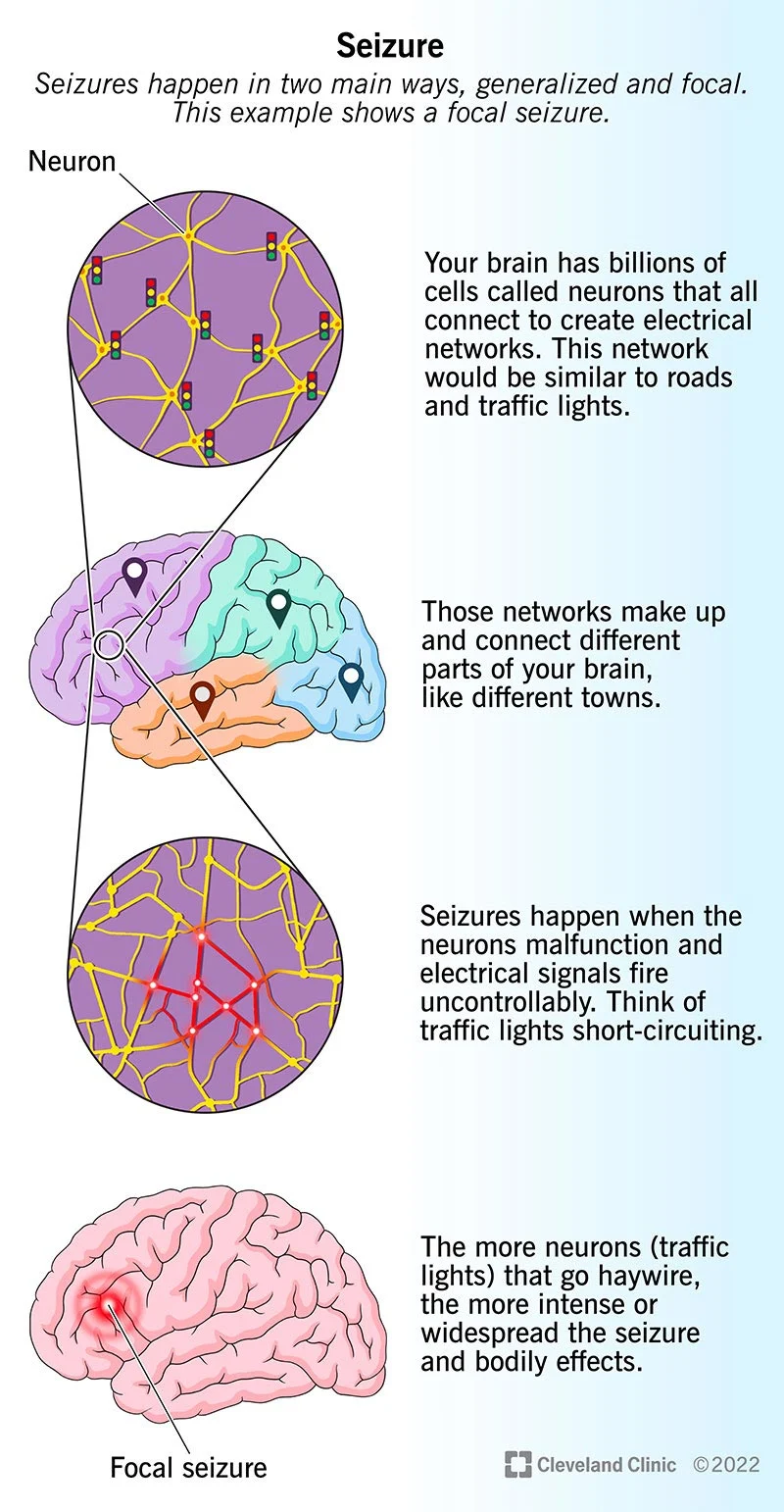

There are certain epileptic seizures, sometimes called "experiential seizures," when a detailed recollection or hallucination of the past suddenly imposes itself upon a patient's consciousness, and pursues a subjectively lengthy and unhurried course, to complete itself in what, objectively, is only a few seconds. These seizures are typically associated with convulsive activity in the brain's temporal lobes, and can be induced, in some patients, by electrical stimulation of certain trigger points on the surface of the lobes. Sometimes such epileptic experiences are suffused with a sense of metaphysical significance, along with their subjectively enormous duration. Dostoyevsky wrote of such seizures:

There are moments, and it is only a matter of a few seconds, when you feel the presence of the eternal harmony. . . . A terrible thing is the frightful clearness with which it manifests itself and the rapture with which it fills you. . . . During these five seconds I live a whole human existence, and for that I would give my whole life and not think that I was paying too dearly.

There may be no inner sense of speed at such times, but at other times--especially with mescaline or LSD--one may feel hurtled through thought-universes at uncontrollable, supraluminal speeds. In "The Major Ordeals of the Mind," the French poet and painter Henri Michaux writes, "Persons returning from the speed of mescaline speak of an acceleration of a hundred or two hundred times, or even of five hundred times that of normal speed." He comments that this is probably an illusion, but that even if the acceleration were much more modest--"even only six times" the normal--the increase would still feel overwhelming. What is experienced, Michaux feels, is not so much a huge accumulation of exact literal details as a series of over-all impressions, dramatic highlights, as in a dream.

But, this said, if the speed of thought could be significantly heightened, the increase would readily show up (if we had the experimental means to examine it) in physiological recordings of the brain, and would perhaps illustrate the limits of what is neurally possible. We would need, however, the right level of cellular activity to record from, and this would be not the level of individual nerve cells but a higher level, the level of interaction between groups of neurons in the cerebral cortex, which, in their tens or hundreds of thousands, form the neural correlate of consciousness.

The speed of such neural interactions is normally regulated by a delicate balance of excitatory and inhibitory forces, but there are certain conditions in which inhibitions may be relaxed. Dreams can take wing, move freely and swiftly, precisely because the activity of the cerebral cortex is not constrained by external perception or reality. Similar considerations, perhaps, apply to the trances induced by mescaline or hashish.

Other drugs--depressants, by and large, like opiates and barbiturates--may have the opposite effect, producing an opaque, dense inhibition of thought and movement, so that one may enter a state in which scarcely anything seems to happen, and then come to, after what seems to have been a few minutes, to find that an entire day has been consumed. Such effects resemble the action of the Retarder, a drug that Wells imagined as the opposite of the Accelerator: The Retarder . . . should enable the patient to spread a few seconds over many hours of ordinary time, and so to maintain an apathetic inaction, a glacier-like absence of alacrity, amidst the most animated or irritating surroundings.

That there could be profound and persistent disorders of neural speed lasting for years or decades first hit me when, in 1966, I went to work in the Bronx at Beth Abraham, a hospital for chronic illness, and saw the patients whom I was later to write about in my book "Awakenings." There were dozens of these patients in the lobby and corridors, all moving at different tempos--some violently accelerated, some in slow motion, some almost glaciated. As I looked at this landscape of disordered time, memories of Wells's Accelerator and Retarder suddenly came back to me. All of these patients, I learned, were survivors of the great pandemic of encephalitis lethargica that swept the world from 1917 to 1928. Of the millions who contracted this "sleepy sickness," about a third died in the acute stages, in states of coma sleep so deep as to preclude arousal, or in states of sleeplessness so intense as to preclude sedation. Some of the survivors, though often accelerated and excited in the early days, had later developed an extreme form of parkinsonism that had slowed or even frozen them, sometimes for decades. A few of the patients at Beth Abraham continued to be accelerated, and one, Ed M., was actually accelerated on one side of his body and slowed on the other.

Dopamine, a neurotransmitter essential for the normal flow of movement and thought, is drastically reduced in ordinary Parkinson's disease, to less than fifteen per cent of normal levels. In post-encephalitic parkinsonism, dopamine levels may become almost undetectable. In ordinary Parkinson's disease, in addition to tremor or rigidity, one sees moderate slowings and speedings; in post-encephalitic parkinsonism, where the damage in the brain is usually far greater, there may be slowings and speedings to the utmost physiological and mechanical limits of the brain and body.

The very vocabulary of parkinsonism is couched in terms of speed. Neurologists have an array of terms to denote this: if movement is slowed, they talk about "bradykinesia"; if brought to a halt, "akinesia"; if excessively rapid, "tachykinesia." Similarly, one can have bradyphrenia or tachyphrenia--a slowing or accelerating of thought.

In 1969, I was able to start most of these frozen patients on the drug L-dopa, which had recently been shown to be effective in raising dopamine levels in the brain. At first, this restored a normal speed and freedom of movement to many of the patients. But then, especially in the most severely affected, it pushed them in the opposite direction. One patient, Hester Y., I observed in my journal, showed such acceleration of movement and speech after five days on L-dopa that "if she had previously resembled a slow-motion film, or a persistent film frame stuck in the projector, she now gave the impression of a speeded-up film, so much so that my colleagues, looking at a film of Mrs. Y. which I took at the time, insisted that the projector was running too fast."

I assumed, at first, that Hester and other patients realized the unusual rates at which they were moving or speaking or thinking but were simply unable to control themselves. I soon found that this was by no means the case. Nor is it the case in patients with ordinary Parkinson's disease, as William Gooddy, a neurologist in England, remarks at the beginning of his book "Time and the Nervous System." An observer may note, he says, how slowed a parkinsonian's movements are, but "the patient will say, 'My own movements . . . seem normal unless I see how long they take by looking at a clock. The clock on the wall of the ward seems to be going exceptionally fast.' " Gooddy refers here to "personal" time, as contrasted with "clock" time, and the extent to which personal time departs from clock time may become almost unbridgeable with the extreme bradykinesia common in post- encephalitic parkinsonism. I would often see my patient Miron V. sitting in the hallway outside my office. He would appear motionless, with his right arm often lifted, sometimes an inch or two above his knee, sometimes near his face. When I questioned him about these frozen poses, he asked indignantly, "What do you mean, 'frozen poses'? I was just wiping my nose."

I wondered if he was putting me on. One morning, over a period of hours, I took a series of twenty or so photos and stapled them together to make a flick-book, like the ones I used to make to show the unfurling of fiddleheads. With this, I could see that Miron actually was wiping his nose but was doing so a thousand times more slowly than normal.

Hester, too, seemed unaware of the degree to which her personal time diverged from clock time. I once asked my students to play ball with her, and they found it impossible to catch her lightning-quick throws. Hester returned the ball so rapidly that their hands, still outstretched from the throw, might be hit smartly by the returning ball. "You see how quick she is," I said. "Don't underestimate her--you'd better be ready." But they could not be ready, since their best reaction times approached a seventh of a second, whereas Hester's was scarcely more than a tenth of a second.

It was only when Miron and Hester were in normal states, neither excessively retarded nor accelerated, that they could judge how startling their speed or slowness had been, and it was sometimes necessary to show them a film or a tape to convince them.

(Disorders of spatial scale are as common in parkinsonism as disorders of time scale. An almost diagnostic sign of parkinsonism is micrographia--minute, and often diminishingly small, handwriting. Typically, patients are not aware of this at the time; it is only later, when they are back in a normal spatial frame of reference, that they are able to judge that their writing was smaller than usual. Thus there may be, for some patients, a compression of space which is comparable to the compression of time. One of my patients, a post-encephalitic woman, used to say, "My space, our space, is nothing like your space.")