An Accident

There have always been anecdotal accounts of people's perception of time when they are suddenly threatened with mortal danger, but the first systematic study was undertaken in 1892 by the Swiss geologist Albert Heim; he explored the mental states of thirty subjects who had survived falls in the Alps. "Mental activity became enormous, rising to a hundred-fold velocity," Heim noted. "Time became greatly expanded. . . . In many cases there followed a sudden review of the individual's entire past." In this situation, he wrote, there was "no anxiety" but, rather, "profound acceptance."

Almost a century later, in the nineteen-seventies, Russell Noyes and Roy Kletti, of the University of Iowa, exhumed and translated Heim's study and went on to collect and analyze more than two hundred accounts of such experiences. Most of their subjects, like Heim's, described an increased speed of thought and an apparent slowing of time during what they thought to be their last moments.

A race-car driver who was thrown thirty feet into the air in a crash said, "It seemed like the whole thing took forever. Everything was in slow motion, and it seemed to me like I was a player on a stage and could see myself tumbling over and over . . . as though I sat in the stands and saw it all happening . . . but I was not frightened." Another driver, cresting a hill at high speed and finding himself a hundred feet from a train which he was sure would kill him, observed, "As the train went by, I saw the engineer's face. It was like a movie run slowly, so that the frames progress with a jerky motion. That was how I saw his face."

While some of these near-death experiences are marked by a sense of helplessness and passivity, even dissociation, in others there is an intense sense of immediacy and reality, and a dramatic acceleration of thought and perception and reaction, which allow one to negotiate danger successfully. Noyes and Kletti describe a jet pilot who faced almost certain death when his plane was improperly launched from its carrier: "I vividly recalled, in a matter of about three seconds, over a dozen actions necessary to successful recovery of flight attitude. The procedures I needed were readily available. I had almost total recall and felt in complete control."

Many of their subjects, Noyes and Kletti said, felt that "they performed feats, both mental and physical, of which they would ordinarily have been incapable."

It may be similar, in a way, with trained athletes, especially those in games demanding fast reaction times. A baseball may be approaching at close to a hundred miles per hour, and yet, as many people have described, the ball may seem to be almost immobile in the air, its very seams strikingly visible, and the batter finds himself in a suddenly enlarged and spacious timescape, where he has all the time he needs to hit the ball.

In a bicycle race, cyclists may be moving at nearly forty miles per hour, separated only by inches. The situation, to an onlooker, looks precarious in the extreme, and, indeed, the cyclists may be mere milliseconds away from each other. The slightest error may lead to a multiple crash. But to the cyclists themselves, concentrating intensely, everything seems to be moving in relatively slow motion, and there is ample room and time, enough to allow improvisation and intricate maneuverings.

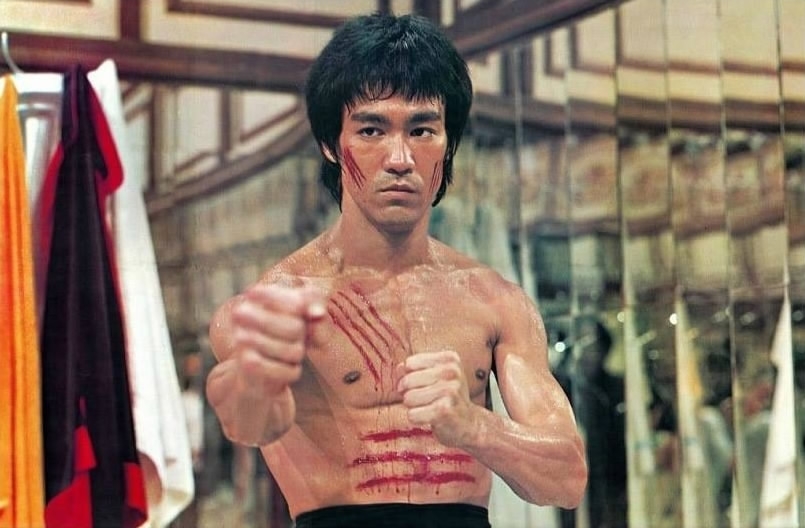

The dazzling speed of martial-arts masters, the movements too fast for the untrained eye to follow, may be executed, in the performer's mind, with an almost balletic deliberation and grace, what trainers and coaches like to call "relaxed concentration." This alteration in the perception of speed is often conveyed in movies like "The Matrix" by alternating accelerated and slowed-down versions of the action.

The expertise of athletes (whatever their innate gifts) is only to be acquired by years of dedicated practice and training. At first, an intense conscious effort and attention are necessary to learn every nuance of technique and timing. But at some point the basic skills and their neural representation become so ingrained in the nervous system as to be almost second nature, no longer in need of conscious effort or decision. One level of brain activity may be working automatically, while another, the conscious level, is fashioning a perception of time, a perception which is elastic, and can be compressed or expanded

In the nineteen-sixties, the American neurophysiologist Benjamin Libet, investigating how simple motor decisions were made, found that brain signals indicating an act of decision could be detected several hundred milliseconds before there was any conscious awareness of it. A champion sprinter may be up and running, and already sixteen or eighteen feet into the race before he is consciously aware that the starting gun has fired. (He can be off the blocks in a hundred and thirty milliseconds, whereas the conscious registration of the gunshot requires four hundred milliseconds or more.) The runner's belief that he consciously heard the gun and then, immediately, exploded off the blocks is an illusion made possible, Libet would suggest, because the mind "antedates" the sound of the gun by almost half a second.

Such a reordering of time, like the apparent compression or expansion of time, raises the question of how we normally perceive time. William James speculated that our judgment of time, our speed of perception, depends on how many "events" we can perceive in a given unit of time.

There is much to suggest that conscious perception (at least, visual perception) is not continuous but consists of discrete moments, like the frames of a movie, which are then blended to give an appearance of continuity. No such partitioning of time, it would seem, occurs in rapid, automatic actions, such as returning a tennis shot or hitting a baseball. Christof Koch, a neuroscientist at Caltech, distinguishes between "behavior" and "experience," and proposes that "behavior may be executed in a smooth fashion, while experience may be structured in discrete intervals, as in a movie." This model of consciousness would allow a Jamesian mechanism by which the perception of time could be speeded up or slowed down. Koch speculates that the apparent slowing of time in emergencies and athletic performances (at least when athletes find themselves "in the zone") may come from the power of intense attention to reduce the duration of individual frames.

The subject of space and time perception is becoming a popular topic in sensory psychology, and the reactions and perceptions of athletes, and of people facing sudden demands and emergencies, would seem to be an obvious field for further experiment, especially now that virtual reality gives us the power to simulate action under controlled conditions, and at ever more taxing speeds.

For William James, the most striking departures from "normal" time were provided by the effects of certain drugs. He tried a number of them himself, from nitrous oxide to peyote, and in his chapter on the perception of time he immediately followed his meditation on Von Baer with a reference to hashish. "In hashish-intoxication," he writes, "there is a curious increase in the apparent time-perspective. We utter a sentence, and ere the end is reached the beginning seems already to date from indefinitely long ago. We enter a short street, and it is as if we should never get to the end of it."

James's observations are an almost exact echo of Jacques-Joseph Moreau's, fifty years earlier. Moreau, a physician, was one of the first to make hashish fashionable in the Paris of the eighteen-forties--indeed, he was a member, along with Gautier, Baudelaire, Balzac, and other savants and artists, of Le Club des Hachichins. Moreau wrote:

Crossing the covered passage in the Place de l'Opera one night, I was struck by the length of time it took to get to the other side. I had taken a few steps at most, but it seemed to me that I had been there two or three hours. . . . I hastened my step, but time did not pass more rapidly. . . . It seemed to me . . . that the walk was endlessly long and that the exit towards which I walked was retreating into the distance at the same rate as my speed of walking.

But while the external world may appear slowed, an inner world of images and thoughts may take off with great speed. One may set out on an elaborate mental journey, visiting different countries and cultures, or compose a book or a symphony, or live through a whole life or an epoch of history, only to find that mere minutes or seconds have passed. Gautier described how he entered a hashish trance in which "sensations followed one another so numerous and so hurried that true appreciation of time was impossible." It seemed to him, subjectively, that the spell had lasted "three hundred years," but he found, on awakening, that it had lasted no more than a quarter of an hour.

The word "awakening" may be more than a figure of speech here, for such "trips" have surely to be compared with dreams. I have occasionally, it seems to me, lived a whole life between my first alarm, at 5 a.m.,and my second alarm, five minutes later.