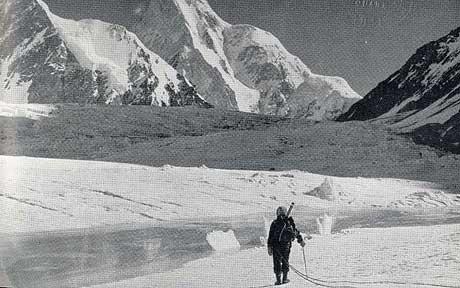

CHARLIE HOUSTON is a legend in mountaineering circles. A physician educated at

both Harvard and Columbia, he had participated in the first ascent of Alaska's Mount

Foraker, in 1934; led the first detailed reconnaissance of the Abruzzi Ridge, in 1938;

and was the first Westerner to enter Nepal's Khumbu Valley, in 1950, spearheading

the route to the south side of Everest. As a flight surgeon in the U.S. Navy, Houston

spent World War II conducting pioneering research on the effects of high altitude on

the human body.

In the summer of 1953, at age 40, he and his oldest friend, Bob Bates— a 42-year-old

Exeter English teacher who had accompanied Houston in 1938 and gone on to develop

much of the Tenth Mountain Division's equipment in World War II—assembled a

team of amateurs for the third American assault on K2. "We chose the expedition

intuitively," Houston explained. "We avoided superstars, people who we thought were

going to put themselves first. We were a group with common ideals, a willingness to

share, and, if I may say so, a singular lack of self-aggrandizement."

The group was made up of eight men. Besides Houston and Bates there was George

Bell, 27, a theoretical physicist at Cornell who had pulled off several first ascents in

Peru; Bob Craig, 28, a philosopher who worked as a ski instructor in Aspen and had

completed the first ascent of the Devil's Thumb, in British Columbia; Craig's friend

Dee Molenaar, 34, a landscape painter and geologist from Seattle who had summited

Alaska's Mount St. Elias; Pete Schoening, 26, a chemical engineer who had led a

successful climbing expedition to the Yukon; Tony Streather, a 27-year-old British

Army captain who'd reached the summit of Pakistan's Tirich Mir in 1951 with a

Norwegian expedition; and finally, an accomplished 27-year-old rock climber from

Iowa named Art Gilkey, who'd researched glaciers in Alaska. They reached Pakistan at

the end of May, in time to receive the news that Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary

had just knocked off Everest. It took them two months to transport their equipment to

K2 base camp, but by early August, Houston and his men had forced their way up the

Abruzzi Ridge to roughly 25,000 feet, where they were pinned down by a massive

storm. After nine days, the team members were finally able to climb out of their tents.

As Art Gilkey emerged, he fell facedown, unconscious.

Examining Gilkey, Houston realized he had thrombophlebitis, a condition in which

blood clots develop in the veins of the legs; if the clots break off and flow to the lungs,

they can cause a pulmonary embolism. At sea level, the condition is extremely serious;

at 25,000 feet, it is virtually a death sentence.

"It was hopeless," Houston recalls, "but we certainly were not going to leave him there

alone—we never even considered that."

All notions of making the summit were forgotten. After an initial attempt to move

Gilkey down the same route they had ascended—which ended when they realized the

entire slope was about to avalanche—Craig and Schoening proposed lowering him

down a rocky ridge to the east. Houston suggested that the rest of the party descend

while he remained with Gilkey; they could return when the weather improved. The

team would have none of it. That night, Houston determined that two clots had indeed

moved into Gilkey's lungs. The next morning, with the storm raging again, they

wrapped him up like a mummy using one of the tents and launched their rescue

effort—the highest ever at the time.

By midafternoon, they'd inched their stricken teammate to within 150 yards of an ice

shelf. To reach it, they would have to haul him across a steep gully, beneath which the

ice fell off almost all the way to the glacier. Schoening stationed himself above Gilkey

on the slope and belayed him by thrusting his ice ax deep into the snow above a large

rock. The rope holding Gilkey was looped around the haft of Schoening's ax, back

across his hips, and through his right hand.

The plan was to pendulum Gilkey across the gully. Before the work began, Craig, who

had nearly been engulfed in a small avalanche a few minutes earlier, unroped from

Molenaar and moved over to the ice shelf for a breather. When Craig unhooked,

Molenaar took the precaution of tying himself to a loose rope connected to Gilkey.

Moments after Molenaar tied in, George Bell, who was also standing above Gilkey, lost

his balance and shot down the slope. As Bell tumbled, he pulled Streather off his feet.

Streather's fall took him directly into a second rope connecting Houston and Bates,

ripping them from their positions. There was nothing to stop the fall of the four

entangled men—except the rope connecting Molenaar to Gilkey, which Streather

snagged as he slid by. Molenaar fell, and now five men rocketed down until the strain

fell on Gilkey—who was connected by a single rope to Schoening.

Schoening leaned into his ax and braced himself for the impact of their fall. The rope

thinned, then drew taut as a steel wire. For the next five minutes, he held all six men.

This would have been remarkable anywhere, but at an altitude at which most people

can barely think, it bordered on the miraculous. It has become the most legendary iceax belay in the history of climbing. "If Pete hadn't held that anchor, Bob Craig would

have been the only survivor," says Molenaar.

When they all came to a halt, Bell was lying precariously close to the drop-off,

Molenaar was bleeding from a gash in his thigh, and Houston lay crumpled at the edge

of the abyss, unconscious. While the rest of the team struggled to right themselves,

Bates soloed down to Houston, whose eyes opened.

"Where are we?" Houston asked. "What are we doing here?"

It was obvious that the battered team could not pull its leader back up the steep rock.

In a last-ditch effort to get the concussed Houston to understand what he had to do on

his own, Bates took his old friend by the shoulders.

"Charlie," Bates said, "if you ever want to see Dorcas and Penny [his wife and

daughter] again, climb up there right now!" Houston obeyed.

It was now essential to get the injured to shelter. Gilkey was anchored securely to his

position in the gully with two ice axes while the others moved to the other side of a

rocky rib to set up a tent. Houston, Bell, Schoening, and Molenaar were placed inside,

then the remaining three returned for Gilkey. When they got back to the gully, the axes

were gone and Gilkey had disappeared. An avalanche had apparently torn through the

chute and taken him with it. "It was," Bates later wrote, "as if the hand of God had

swept him away."

The next morning, after a horrendous night, the team found themselves climbing

down through a tangle of chopped ropes and pieces of sleeping bag. Houston was first

on the rope. "It was obvious that we were climbing down the same route that Art had

taken, and that we were climbing through Art's blood," he recalls. "Blood and blood

and blood...We didn't talk about that for a very, very long time."

Four days later, the seven survivors stumbled into base camp, as stunned by the

unlikely fact that they were alive as by the loss of their friend. The porters erected a

cairn, dedicated to Gilkey, on a prominent point of rock 200 feet above the glacier

floor. It stands there to this day.

On the aftenoon after my tour of the dead, I clambered up to the Gilkey

Memorial, a pile of ocher rock now festooned with dozens of plates and saucepan lids

inscribed with eulogies to all the men and women who have died here. Below, I could

see a procession of Pakistani guides bearing the bodies of six Japanese climbers who

had been killed by an avalanche in 1997. Like Dudley Wolfe, they had recently

emerged from the glacier. The guides stacked the corpses, wrapped them in plastic,

then piled ice on top to keep them cool until a funeral pyre could be assembled from

wood they had carried to base camp. As the wind kicked up, the plates and lids began

rattling against the stone, beating out a mournful, otherworldly cadence.

At that moment, K2 seemed little more than an abattoir—a place linked inextricably

with death. It was only months later, after I had returned home and met Charlie

Houston for the first time, that it occurred to me that K2 might also embrace another

quality—a dimension of redemptive grace that extends beyond the sport of

mountaineering.

This summer marked the 50th anniversary of Art Gilkey's death. George Bell died in

2000, but the remaining six teammates still convene for reunions, united by a sense of

solidarity about what they did on K2. "There was nothing heroic about it," insists

Houston, who turned 90 in August. "It was just a job that had to be done. We weren't

counting how many people would be bereft if we died, because we weren't figuring on

dying. That's why I don't accept people who call us heroes. What else were we to do?"

Houston's unsentimental attitude is admirable, but it fails to do justice to the fact that

he and his men did, in fact, have a choice: They could have abandoned Gilkey to a fate

that was almost certainly inevitable. Their selflessness in refusing even to consider

such a thing may not qualify as heroism in their eyes, but to some it defines them in

terms that cannot be other than heroic.

"The year after Charlie and his team came home," says Jim Curran, the K2 historian,

"the Italians finally succeeded in reaching the top—but it is Houston's expedition

that remains the touchstone of all that is best in mountaineering. Unfortunately, the

world has since slid past this ideal. Events in climbing today are totally silly,

particularly on Everest. But what those men did on K2 in 1953 was incredible. It is

now one of the great legends of the mountains. In the annals of Himalayan climbing,

there is nothing finer than this."

What that legend suggests is that K2 may well be greater than Everest. Not because it's

technically harder or imparts more lyrical visions to those who climb it, but because,

through the actions of Houston and his men, K2's signature narrative achieved an

expression weightier than mere triumph. "I have great respect for the Italians who

summited K2 for the first time in 1954," says Reinhold Messner, "but even greater

respect for the Americans and the way they failed in 1953. They were decent. They

were strong. And they failed in the most beautiful way you can imagine. This is

inspiration for a lifetime."

If Everest is a mountain that supposedly personifies the highest level of human

achievement—achievement that each year is cheapened by ever less meaningful

distinctions—then K2 is a mountain that embodies the supreme level of human

failure. Failure imbibed to the fullest measure. Failure that cuts to the bone. And

failure, too, that through some paradoxical alchemy transcends carnage by

transforming those who possess the resilience and the honor to weather the ordeal.

This is the secret to K2.